What Americans Can Learn From Hungary’s Election

05/2022 | Reading time: 12 minutes

05/2022 | Reading time: 12 minutes

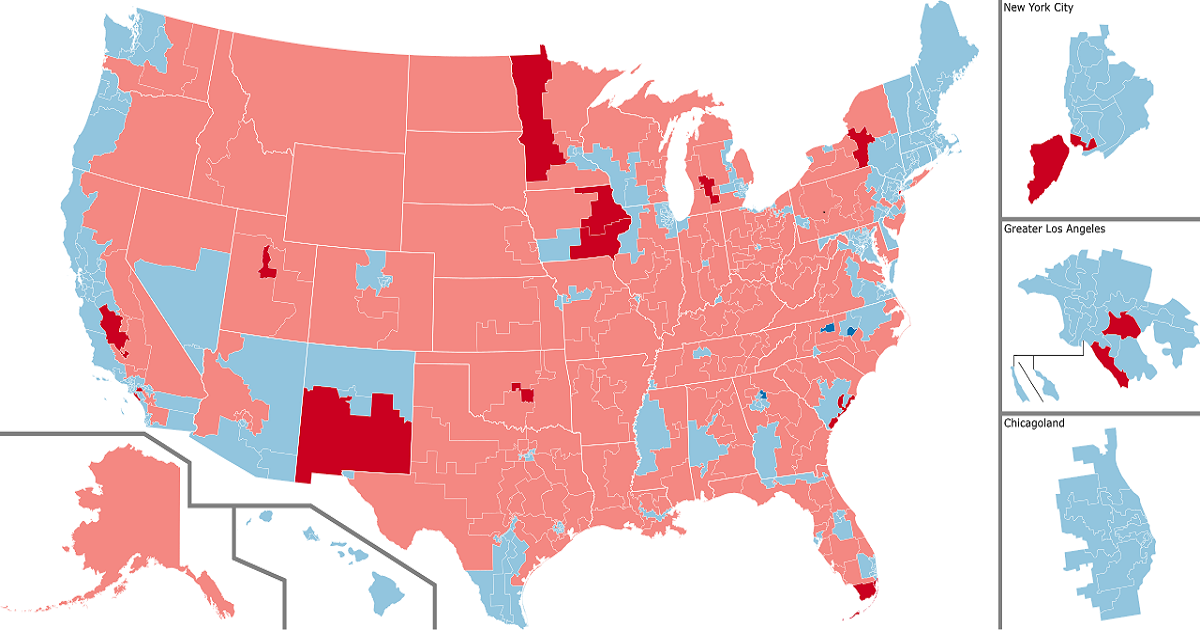

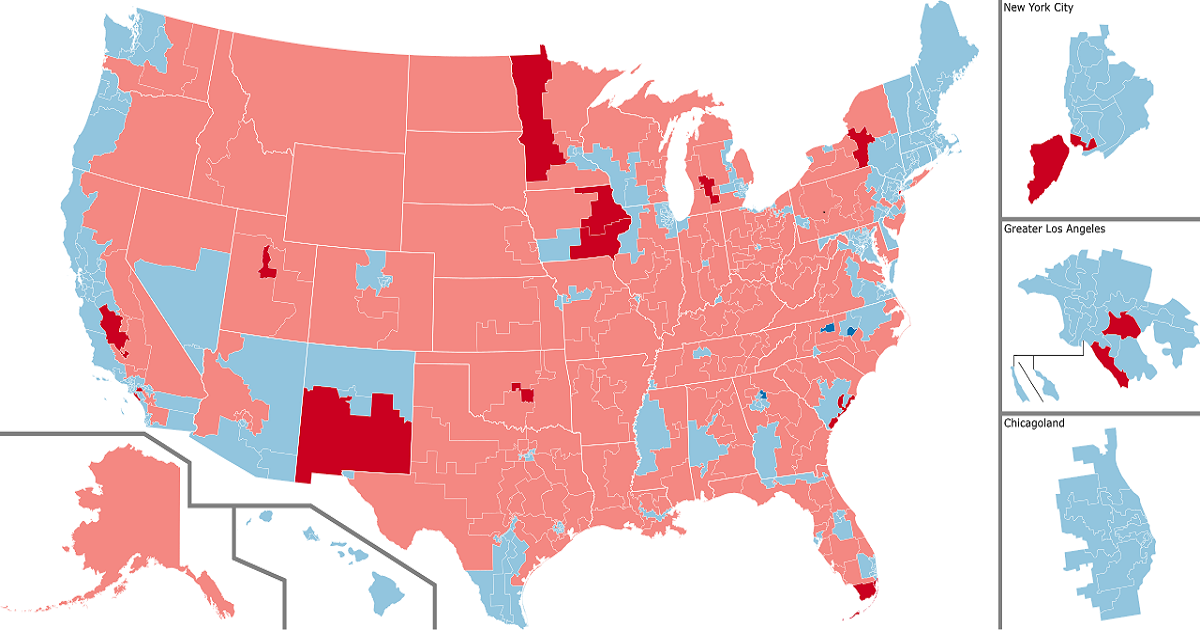

In the United States, as the midterm election season shifts into high gear, dozens of primary elections are taking place over the next few weeks and months which will define the direction of states and localities for decades to come. With 12 primaries in May, including a highly contested Georgia primary on May 24, 17 primaries in June, and 14 in August, these primaries will choose the best candidates from any given party to campaign for open seats on election day, November 8th. With razor thin margins holding the Democratic majorities in the House, where Republicans only need 5 seats to flip the majority, and Senate, where the Republicans only need one seat, the Democrats are defending against a surge in a Republican party which has moved further right than many expected. In an era of American politics which seems to be defined daily by some new and unexpected political move, we are seeing exceptional strategies being implemented by potential candidates.

These exceptional strategies, however, must be implemented with an eye to the future, not simply toward the current moment. American politics is at its worst when it is not observing history to inform our future, and Hungary’s most recent election gives the current crop of potential American candidates important information.

Hungarian readers will surely be very familiar with the most recent parliamentary elections, but for non-Hungarian readers, a quick summation. The April 2022 Hungarian election was an unprecedented attempt to unseat the conservative Fidesz party from their near-decade long command of parliament. The approach saw a broad coalition built between mostly liberal opposition parties to create the Egységben Magyarországért united election list party, or United For Hungary (EM) with Péter Márki-Zay as its leader, however, leaving these political parties as separate groups under the same tent eventually presented its own issues.

The “big tent” united electoral list encompassed similar views but all had an overarching goal: beat Fidesz. Many of these groups in the coalition fell into more liberal sides of the political spectrum, but the sticking point ended up being that both extreme sides of the spectrum were represented under this big tent, including the Movement for a Better Hungary, or Jobbik, formerly one of the most extreme right-wing political parties described as being populist-nationalists. Jobbik has attempted to move closer to the center of the political spectrum since 2016, but remained plagued by antisemitic scandals. The inclusion of Jobbik was necessary for the coalition to gain ground needed to unseat Fidesz but unnerved many liberals. In the end, however, Jobbik was not the most interesting story.

This brings view back to the United States, where across the country the liberal side has been looking for new ways to defeat a growing extreme-right movement and nationalist sentiment amidst record inflation and disruption. This has included safe strategies, such as positioning themselves as the only party which cares for the people, risky strategies such as running ads supporting candidates they believe are easy to beat, like Doug Mastriano in Pennsylvania, or allying themselves with independent candidates to win a potential category of voters which may be unreachable by traditional means. It is that last strategy which bears remembrance of Hungary’s recent election.

When the dust settled after April 3 in Hungary the results were clear: Fidesz had resoundingly held onto power with 54.13% of the vote and even increased their seats in Parliament. The coalition party of United For Hungary received only 34.44% of the vote, and a surprise was found that the party Mi Hazánk Mozgalom, or Our Homeland Movement, a far-right party won 5.88%. Whereas Jobbik unnerved some liberals in the United For Hungary coalition by being an extreme right group, Our Homeland Movement (MHM) is an even farther extreme right group which has been likened to believing neo-fascist ideals and came to more prominence during the pandemic for their anti-vaccine stance.

The reason for MHM’s success, bolstered by visibility due to the pandemic, was that Jobbik had moved more to the center to align with United for Hungary and was not right-wing enough anymore. This disenfranchised the right-wing elements of their party and caused them to look for another group that promoted their ideals. This migration is an important factor to keep in mind in a surprising place: Utah.

Evan McMullin, a former Republican staffer, rose to notoriety in 2016, launching an independent campaign for President as a counterweight to the extremist “MAGA” type-politicians which had entered his party countrywide and ran their elections based on fear instead of substance. McMullin campaigned for only three months, but garnered half a million votes during the election in places where he was listed on the ballot. Now, McMullin is running again as an independent, this time to unseat Utah Senator Mike Lee, and this time he is doing it in unspoken coalition with the Democrats.

The Democrats have a very weak foothold in Utah, with only 35% of the vote normally going their way, and will not run a candidate this election cycle, the plan being to give McMullin the maximum number of votes without splitting the liberal and independent vote. This is a savvy strategy, and one that many are calling to be used in other states without strong Democratic reach if it works. But if Hungary is any indication: the parties must pay attention to the needs of the voters.

It is not unrealistic to imagine that Evan McMullin’s generally conservative views would disenfranchise extreme liberal voters, or cautiously liberal independents, in the same way United For Hungary disenfranchised those who voted for Our Homeland Movement. The implied support for an independent candidate must be followed up with reasons why this is a net good for both independents and liberals, not simply tacit endorsement and an acknowledgement that this candidate is “not the other guy.” Democrats saw last year in Virginia that simply running a candidate as “not the other guy” does not work, and United For Hungary, which campaigned largely on being “not Fidesz” over firm policy stances, learned the same lesson on a much larger scale.

Hungary proved that expecting a political party to act as a unified entity, instead of a diverse group of individuals with different needs across a spectrum, does not work. United For Hungary’s slogan of “let Hungary belong to us all” sounded nice but did not listen to all of its voters. The liberal and independent wings of the United States must heed these lessons as they go into an election season that will potentially define the country for decades to come. The Democrats, if they choose to pursue a coalition method with independent candidates, must sing from the rooftops why this is the best approach and convince the electorate that working together is the correct choice. Otherwise, it is likely we will see more fractures as voters look to be heard. Conversely, Republicans, which have lost the popular vote across the United States in every Presidential election since 2004, must work to ingratiate themselves with more moderate voters instead of continuing to move further right lest they risk losing real ground to the independent and liberal coalitions. If the Democrats, independents, and Republicans in the United States want the country to belong to everyone, they must listen to everyone and work for them.

John Kelly is an AJKC author and Visiting Fellow at German Marshall Fund.

The opening pic is by Infinitesimall/Wikimedia.

If you like it please share

Please kindly note that this site, similarly to most of the sites, uses cookies. To provide you with the best possible experience, the cookie settings on this website are set to "allow all cookies." If you continue without changing these settings, you consent to our cookie policy. If you would like to, you can change your settings at any time. More details